When Was The Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painted

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508-12, fresco (Vatican, Rome)

Visiting the Chapel

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican city, Rome) (photo: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC Past iii.0)

To any visitor of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel, two features become immediately and undeniably credible: 1) the ceiling is really high up, and 2) there are a lot of paintings up there. Because of this, the centuries take handed downward to united states an prototype of Michelangelo lying on his back, wiping sweat and plaster from his eyes every bit he toiled away year afterward year, suspended hundreds of feet in the air, begrudgingly completing a commission that he never wanted to accept in the get-go place.

Fortunately for Michelangelo, this is probably not truthful. Just that does zilch to lessen the fact that the frescoes, which take upwardly the entirety of the vault, are among the most important paintings in the world.

Michelangelo, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican Metropolis, Rome; photo: public domain)

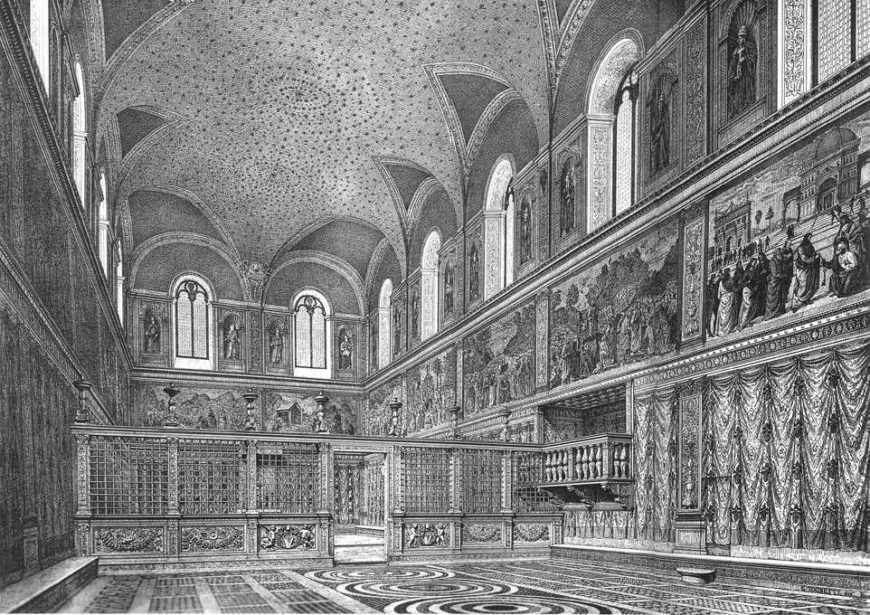

Reconstruction of the Sistine Chapel prior to Michelangelo's frescoes (photo: Sailko, public domain)

For Pope Julius II

Michelangelo began to work on the frescoes for Pope Julius Two in 1508, replacing a blueish ceiling dotted with stars. Originally, the pope asked Michelangelo to paint the ceiling with a geometric ornamentation, and place the twelve apostles in spandrels around the decoration. Michelangelo proposed instead to pigment the Old Testament scenes now found on the vault, divided by the fictive architecture that he uses to organize the composition.

![Diagram of the subjects of the Sistine Chapel [1] (photo: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/1280px-Sistine_Chapel_ceiling_diagram.svg-870x468.png)

Diagram of the subjects of the Sistine Chapel [1] (photo: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The subject area of the frescoes

The narrative begins at the altar and is divided into three sections. In the outset 3 paintings, Michelangelo tells the story of The Creation of the Heavens and World; this is followed by The Creation of Adam and Eve and the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden; finally is the story of Noah and the Swell Overflowing.

Ignudi, or nude youths, sit down in fictive architecture around these frescoes, and they are accompanied by prophets and sibyls (ancient seers who, according to tradition, foretold the coming of Christ) in the spandrels. In the iv corners of the room, in the pendentives, 1 finds scenes depicting the Salvation of Israel.

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (The holy see, Rome; photograph: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY 3.0)

The Deluge

Although the most famous of these frescoes is without a dubiety, The Cosmos of Adam, reproductions of which take go ubiquitous in modern civilization for its dramatic positioning of the two awe-inspiring figures reaching towards each other, not all of the frescoes are painted in this style. In fact, the offset frescoes Michelangelo painted contain multiple figures, much smaller in size, engaged in complex narratives. This can best be exemplified by his painting of The Deluge.

Michelangelo, The Drench, Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Michelangelo, CC0)

Michelangelo, The Deluge (detail), Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1508–12, fresco (The holy see, Rome; photo: Michelangelo, CC0)

In this fresco, Michelangelo has used the physical space of the water and the sky to carve up iv distinct parts of the narrative. On the right side of the painting, a cluster of people seeks sanctuary from the rain under a makeshift shelter. On the left, fifty-fifty more people climb upwards the side of a mount to escape the rising water. Centrally, a small boat is about to capsize because of the unending downpour. And in the background, a team of men work on edifice the arc—the only hope of salvation.

Michelangelo, Creation scenes, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican City, Rome) (photograph: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Upward close, this painting confronts the viewer with the agony of those almost to perish in the alluvion and makes one question God's justice in wiping out the entire population of the earth, save Noah and his family unit, considering of the sins of the wicked. Unfortunately, from the floor of the chapel, the use of small, tightly grouped figures undermines the emotional content and makes the story harder to follow.

A shift in style

In 1510, Michelangelo took a yearlong break from painting the Sistine Chapel. The frescoes painted after this break are characteristically unlike from the ones he painted before information technology, and are allegorical of what we remember of when nosotros envision the Sistine Chapel paintings. These are the paintings, like The Cosmos of Adam, where the narratives take been pared down to but the essential figures depicted on a awe-inspiring calibration. Because of these changes, Michelangelo is able to convey a strong sense of emotionality that can be perceived from the flooring of the chapel. Indeed, the imposing effigy of God in the three frescoes illustrating the separation of darkness from light and the creation of the heavens and the earth radiates ability throughout his torso, and his dramatic gesticulations aid to tell the story of Genesis without the addition of extraneous detail.

The Sibyls

Michelangelo, Delphic Sibyl, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508–12, fresco (Vatican Metropolis, Rome; photograph: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY iii.0)

This new monumentality can also be felt in the figures of the sibyls and prophets in the spandrels surrounding the vault, which some believe are all based on the Dais Torso, an ancient sculpture that was then, and remains, in the Vatican's drove. Ane of the most celebrated of these figures is the Delphic Sibyl.

The overall round composition of the body, which echoes the contours of her fictive architectural setting, adds to the sense of the sculptural weight of the figure.

Her arms are powerful, the heft of her body imposing, and both her left elbow and knee joint come into the viewer'south space. At the same time, Michelangelo imbued the Delphic Sibyl with grace and harmony of proportion, and her watchful expression, as well as the position of the left arm and right paw, is reminiscent of the creative person'due south David.

Michelangelo, Libyan Sibyl, c. 1511, fresco, part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (Vatican Museums; photograph: Jörg Bittner Unna, CC BY three.0)

The Libyan Sibyl is also exemplary. Although she is in a contorted position that would be nearly impossible for an actual person to concord, Michelangelo even so executes her with a sprezzatura (a deceptive ease) that will become typical of the Mannerists who closely modelled their work on his.

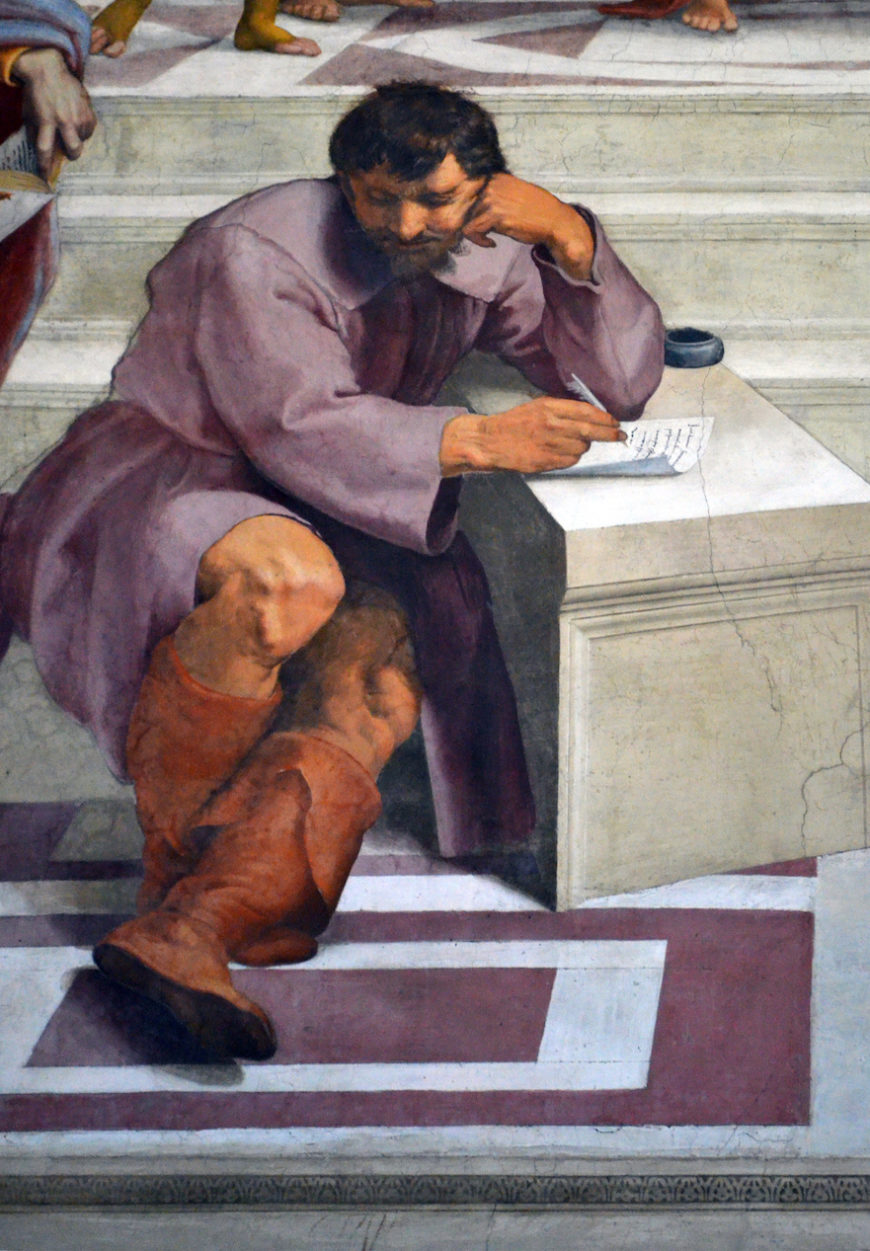

Information technology is no wonder that Raphael, struck past the genius of the Sistine Chapel, rushed back to his School of Athens in the Vatican Stanze and inserted Michelangelo's weighty, monumental likeness sitting at the bottom of the steps of the school.

Heraclitus, whose features are based on Michelangelo'due south and his seated pose is based on the prophets and sibyls from Michelangelo's frescoes on the Sistine Chapel Ceiling (detail), Raphael, School of Athens, 1509–11, Stanza della Segnatura (State of the vatican city, Rome; photo: Darafsh, CC By-SA 3.0)

Legacy

Michelangelo completed the Sistine Chapel in 1512. Its importance in the history of fine art cannot be overstated. It turned into a veritable academy for immature painters, a position that was cemented when Michelangelo returned to the chapel twenty years later to execute the Last Judgment fresco on the altar wall.

The chapel recently underwent a controversial cleaning, which has one time over again brought to low-cal Michelangelo's gem-similar palette, his mastery of chiaroscuro, and boosted iconological details which go on to captivate modernistic viewers even 5 hundred years after the frescoes' original completion. Not bad for an creative person who insisted he was not a painter.

Notes:

[one] The diagram neglects the subject of the four corner paintings indicated in lavender. The four scenes represent the salvation of the Jewish people.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Vatican Museums

Panorama of the Sistine Chapel from the Vatican

Source: https://smarthistory.org/michelangelo-ceiling-of-the-sistine-chapel/

Posted by: hardytogre1977.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Was The Sistine Chapel Ceiling Painted"

Post a Comment